(Originally printed in Bass Player 1/14)

Sins Of The Fathers

by Ed Friedland

Bassists of my generation and older remember a time when the vintage instruments we currently treasure were just basses—we even thought some of them needed a little work to be playable. Super high volume levels, heavy effects use, and techniques like slap/funk changed the demands we placed on the instrument—so we modded them. When you see an ad for a genuine 1966 Fender Precision for $1,200, odds are it was a “lab rat” for a well-meaning Boomer like myself. Maybe it was the climate of experimentation, the eternal quest for the ultimate, or perhaps it was the “rarefied air” of the times—but the victims remain, many beyond hope. But it’s not all bad news folks, although these not-yet treasures were sacrificed to the volcano, they fueled the evolution of the instrument.

In a sense, the electric bass invited hot-rodding from the very start. As performance volume levels increased (due in no small part to the instrument itself), bass players looked for ways to improve its function. When the original single-coil pickup from the 1951 Fender Precision was modified in 1957 to the split-coil version we use today, the goal was better tone, and higher volume—the driving force behind most bass developments. Around 1969, Alembic changed the game with active electronics, exotic woods, and high-end luthiery, but due to the premium price point, many of us simply tried to “Alembicize” our Fenders. The industry also took notice—when examining each of Leo Fender’s successive instrument designs (MusicMan and G&L), you might imagine he was paying attention to the way people modified his earlier work. Each revision of his bass guitar reflected the new developments and contributed a few of their own. Other new brands came about that used these new ideas as their starting point.

Let’s take a step back in time and setup a typical scenario: It’s 1979 and you’ve just bought a used 1966 Fender P bass. As it’s only 13 years old, and you’re only 20, it’s future value was not a consideration, in fact—because it’s not “Pre-CBS”, it’s no big deal. When Fender introduced the natural finish on ash bodies in 1970, it was no doubt a response to all the basses that lost their pigment to a can of Zip Strip in the late 60s—and so, we have:

Step 1: Go Natural—a classic DIY that often produced sloppy results, and prolonged exposure to noxious fumes (coincidence?). Of course you’ll have to take the bass apart, which means you’ll have to put it back together, (make sure you remember where the wires go, dude). Today, information on how to refinish an instrument is a few clicks away, but back then it was often a spontaneous decision carried out with no guidance: [In Tommy Chong voice] “Hey man, like I bet this custom color sea-foam green ’66 P Bass would look far-out if I stripped it natural man! Wow, like, I gotta do the headstock too man!” An oil finish was/is a smart way to go if you’re doing the DIY—applying many coats of oil to a well-prepped body is feasible, but spraying lacquer or nitro correctly is beyond the average person’s capabilities—not to say some of us didn’t try. And then of course, a can of spray paint often seemed like a good idea.

Step 1: Go Natural—a classic DIY that often produced sloppy results, and prolonged exposure to noxious fumes (coincidence?). Of course you’ll have to take the bass apart, which means you’ll have to put it back together, (make sure you remember where the wires go, dude). Today, information on how to refinish an instrument is a few clicks away, but back then it was often a spontaneous decision carried out with no guidance: [In Tommy Chong voice] “Hey man, like I bet this custom color sea-foam green ’66 P Bass would look far-out if I stripped it natural man! Wow, like, I gotta do the headstock too man!” An oil finish was/is a smart way to go if you’re doing the DIY—applying many coats of oil to a well-prepped body is feasible, but spraying lacquer or nitro correctly is beyond the average person’s capabilities—not to say some of us didn’t try. And then of course, a can of spray paint often seemed like a good idea.

Since the bass is apart already, and the finish is sort of dry, what else can we do?

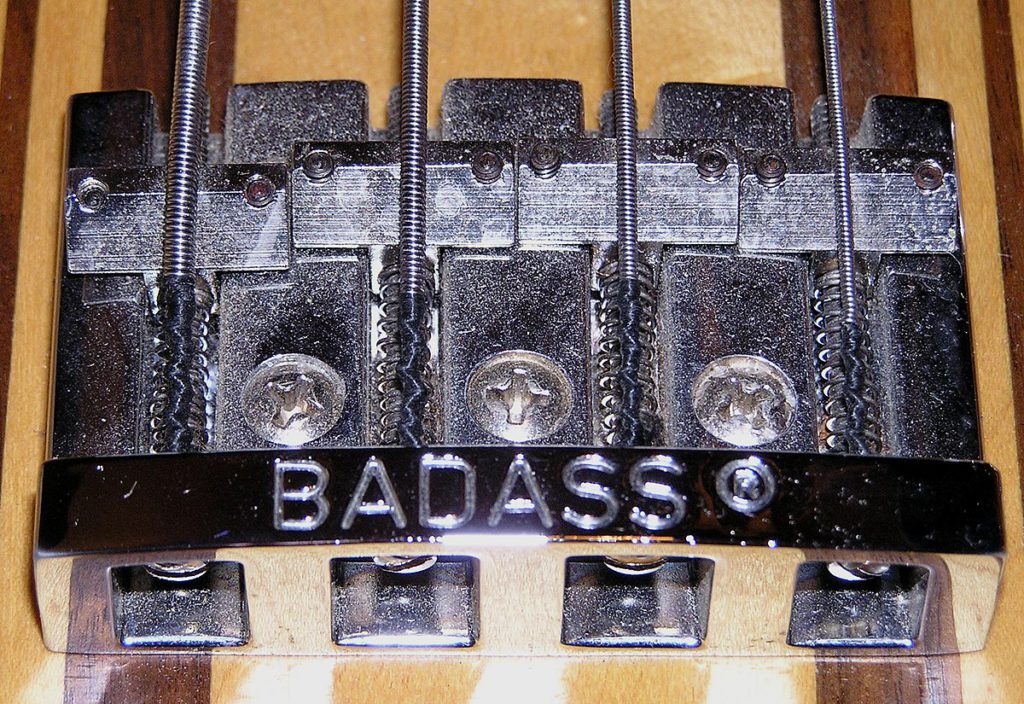

Step 2: High Mass Bridge mod—back in 1979, you were most likely to put on a Leo Quan Badass bridge. The original Badass I required routing the body to seat the bridge into the wood. The higher mass, and greater coupling with the wood helped sustain, but it was basically a non-reversible mod (though some restorations have been successful), and for the DIYer, it was another invitation to disaster with the router—or worst case scenario: a chisel! The Badass II required no routing or drilling and was the most likely candidate back in the stone ages.

Step 2: High Mass Bridge mod—back in 1979, you were most likely to put on a Leo Quan Badass bridge. The original Badass I required routing the body to seat the bridge into the wood. The higher mass, and greater coupling with the wood helped sustain, but it was basically a non-reversible mod (though some restorations have been successful), and for the DIYer, it was another invitation to disaster with the router—or worst case scenario: a chisel! The Badass II required no routing or drilling and was the most likely candidate back in the stone ages.

Step 3: Brass Nut. I haven’t discussed this mod earlier, as it has lost mass appeal, but in 1979? Hell yes! A brass nut increases sustain to a point, but mostly gives the open strings a tone more similar to fretted notes. This was a mod most of us brought to a professional. Good news—it’s reversible.

Step 3: Brass Nut. I haven’t discussed this mod earlier, as it has lost mass appeal, but in 1979? Hell yes! A brass nut increases sustain to a point, but mostly gives the open strings a tone more similar to fretted notes. This was a mod most of us brought to a professional. Good news—it’s reversible.

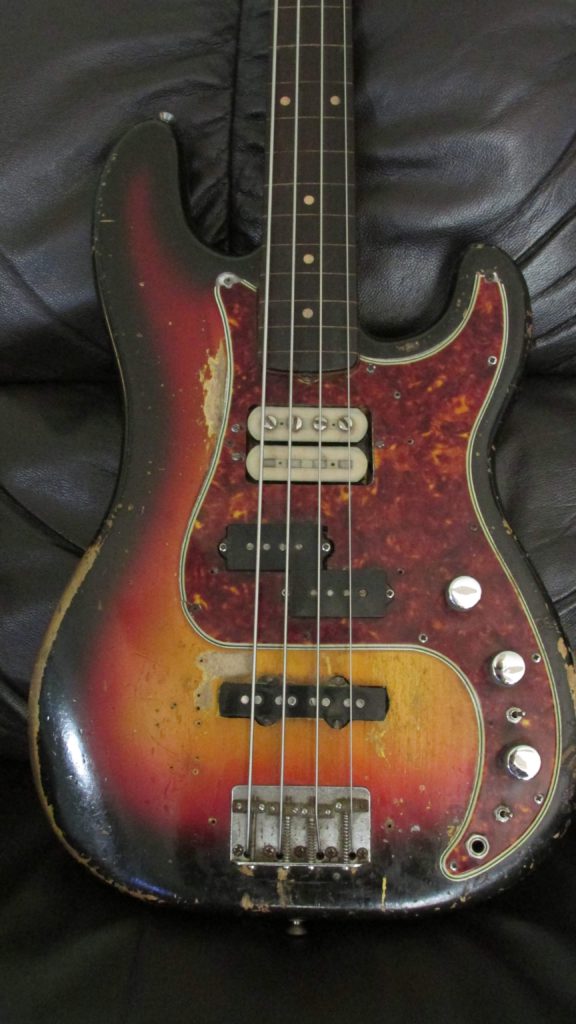

Step 4:P/J! Well, who doesn’t want “the best of both worlds”? Having a J pickup cut into a P bass can definitely add to it’s capabilities, but if we knew back then how we were destroying the value of our instruments, would we have still done it? This mod also had a pretty steep learning curve, some of them turned out great, but many were ruined more than once. In some cases, we simply chose to replace the existing pickup with another brand. You’ll see a lot of old modded basses with the DiMarzio Model P pickup, and mods from the 80s with EMGs and Bartolinis.

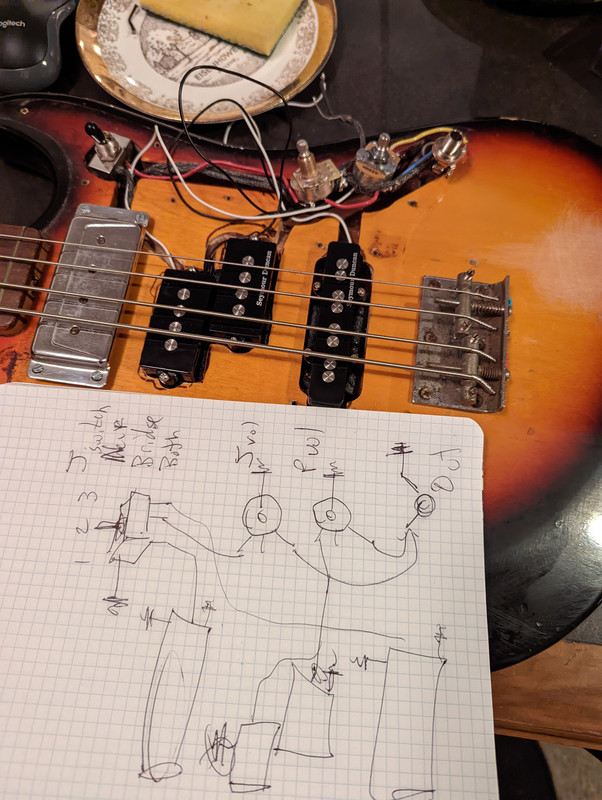

Step 5 was inevitable: Mess with the wiring. Even with a single split-coil pickup P bass, you could still install a series/parallel switch to drastically change the character of the bass. The two coils are wired together in series mode, meaning one coil “feeds” into the other. Switching them to parallel creates a bit of a volume drop, but also scoops out a little midrange. It’s not necessarily better or worse, just different. Where this mod really makes sense is in the P/J configuration where having the P pickup wired in parallel makes it blend a little better with the J pickup. This was also a common mod on J basses, and at some point Fender tried to implement this feature on both models with the ill-fated S-1 switch. Another classic mod, thankfully long forgotten is the phase switch. When you have two coils, you can reverse their phase relationship, creating one of the most useless, sackless, nasal tones imaginable! And yet, we did that. No one really knows why.

Step 5 was inevitable: Mess with the wiring. Even with a single split-coil pickup P bass, you could still install a series/parallel switch to drastically change the character of the bass. The two coils are wired together in series mode, meaning one coil “feeds” into the other. Switching them to parallel creates a bit of a volume drop, but also scoops out a little midrange. It’s not necessarily better or worse, just different. Where this mod really makes sense is in the P/J configuration where having the P pickup wired in parallel makes it blend a little better with the J pickup. This was also a common mod on J basses, and at some point Fender tried to implement this feature on both models with the ill-fated S-1 switch. Another classic mod, thankfully long forgotten is the phase switch. When you have two coils, you can reverse their phase relationship, creating one of the most useless, sackless, nasal tones imaginable! And yet, we did that. No one really knows why.

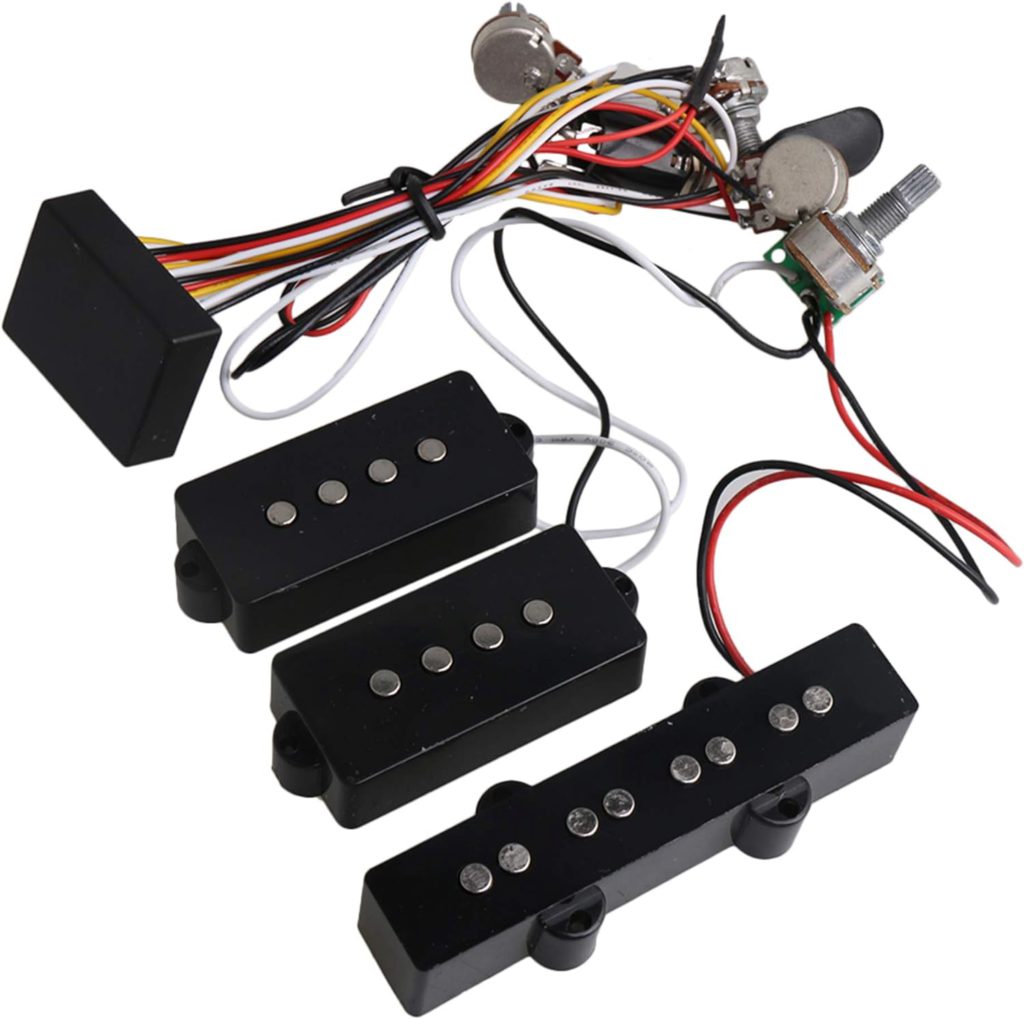

Step 6: Go Active: Although Alembic and MusicMan were building active basses, aftermarket preamps were few and far between in those days, Stars Guitars built an early onboard preamp, famously installed in Marcus Miller’s Jazz bass by Roger Sadowsky. The increased output and tone control gave the J a new voice, but it often required major routing. Soon after, EMG and Bartolini began offering a wide variety of active pickups and preamps, and were eventually joined by many other companies.

Step 6: Go Active: Although Alembic and MusicMan were building active basses, aftermarket preamps were few and far between in those days, Stars Guitars built an early onboard preamp, famously installed in Marcus Miller’s Jazz bass by Roger Sadowsky. The increased output and tone control gave the J a new voice, but it often required major routing. Soon after, EMG and Bartolini began offering a wide variety of active pickups and preamps, and were eventually joined by many other companies.

Step 7: Messing with the neck. This could mean simply converting the bass to fretless, but it was not unheard of for people to take a big P bass neck and narrow it to a Jazz width. While I’ve never done this myself, I have owned several basses that had the neck narrowed. To do this, the frets had to be pulled, and the neck reshaped by a luthier—sometimes it turned out great, other times—not so much.

Step 7: Messing with the neck. This could mean simply converting the bass to fretless, but it was not unheard of for people to take a big P bass neck and narrow it to a Jazz width. While I’ve never done this myself, I have owned several basses that had the neck narrowed. To do this, the frets had to be pulled, and the neck reshaped by a luthier—sometimes it turned out great, other times—not so much.

Step 8 often occurred when adding new pickups, a preamp, or changing other aspects of the wiring—new pots. The old ones were probably fine, but new ones are better right? Maybe, except we never imagined that the original pots—even the original solder joints could one day increase the value of a vintage instrument.

Step 8 often occurred when adding new pickups, a preamp, or changing other aspects of the wiring—new pots. The old ones were probably fine, but new ones are better right? Maybe, except we never imagined that the original pots—even the original solder joints could one day increase the value of a vintage instrument.

Taking in the totality of our handiwork, what we end up with is: A 1966 Precision bass stripped to a natural finish, with a Badass bridge, brass nut, a set of Dimarzio P/J pickups (white covers of course), a series/parallel switch, a phase switch (you know you want it), Bartolini preamp (requiring much routing under the pickguard, a battery compartment, and a side-mounted input jack), swapped out pots, and a shaved-down Jazz-width fretless neck. If left original, the bass could fetch between $5,000 to $12,000 depending on condition and color. After these mods however, you might get $1,750 to $3,000 depending on condition and the gullibility of the buyer. When looked at in purely economic terms, we screwed up—but our intentions were good. And while you will know us from the trail of dead collector’s items we left behind, we did in fact do the bass world a favor. The later work of Leo Fender crystalized many of these experimental ideas into a reliable, affordable production line instrument, Roger Sadowsky forged the premium, modified Fender-style instrument platform we all love today, and virtually every non-Fender styled instrument on the market can trace some of its features back to the “mod years”. No longer do you have to ruin a perfectly good bass guitar to get what you want, you can just buy it that way. You’re welcome. However, if you are currently in possession of an original 1966 P bass and are thinking of trying any of this—stop. Put it down, step away from the bass, and get some help!

Love it, Ed.

Thanks!

Awesome job Ed! Love it.

Good read, thank you so much! But those were the days and I have been restoring some of these mods for the last two decades.